FROM THE ORDINARY TO THE ETERNAL: THE ART OF CHRISTINA MORALI

- Portes Magazine

- Dec 13, 2025

- 6 min read

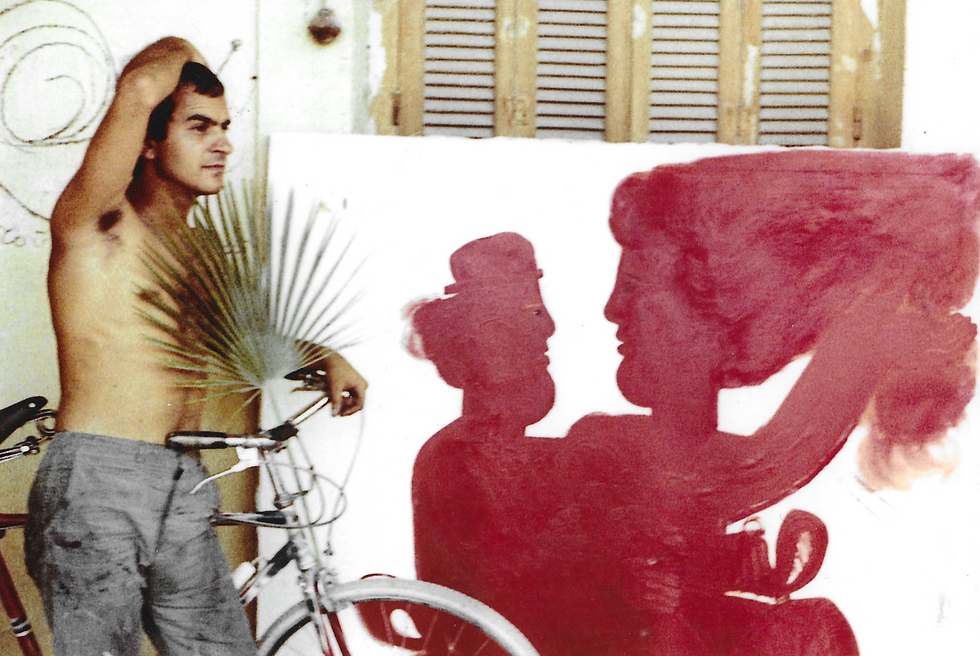

Ceramic artist Christina Morali merges a rich family legacy of artistry with a lifelong dedication to applied arts and design. Growing up surrounded by creative influences, including her uncle Yannis Moralis, she learned to embrace evolution in her work, moving seamlessly between ceramics, sculpture, and functional objects while experimenting with materials, textures, and forms.

Morali is particularly known for her inventive recreations of vintage brands, porcelain explorations, and everyday objects reimagined through a contemporary lens, combining meticulous craftsmanship with playful curiosity. Influenced by the revolutionary energy of 1970s London and shaped by her Greek heritage, her work reflects a balance of tradition, innovation, and constant reinvention, capturing both the tactile beauty of ceramics and the narrative power of design.

PORTES EDITOR: You were raised in a family of artists. Do you recall anyone discussing the unique challenges artists face—creative blocks or deeper struggles?

CHRISTINA MORALI: That’s a great question. When you grow up in a family of artists—or even architects, as in my case—it’s different. My mother also painted. Interestingly, my father was in the Royal Navy, as it was called then, and he was very progressive. No one in my family ever discouraged me. I always knew I wanted to study art. I think I gave them the signs early on that I was naturally drawn to art. I never questioned it. It was just a part of life. When you grow up surrounded by art, it feels very natural—you don’t have to force it, and your family doesn’t push or resist it either. I was ready for the Fine Arts exams, but I let it go. I started becoming interested in applied arts.

My uncle Yannis Moralis was the only famous painter in Greece who worked so much across multiple media. He applied his distinctive blend of classical harmony and modern abstraction not only in painting but also in designing architectural murals, book covers, and stage sets for the National Theatre. He was especially famous for integrating the human figure with geometric forms, and he also created notable works in ceramics and textile design, such as wall compositions for public buildings and decorative motifs for fabric patterns.

He didn’t just “experiment”—he truly engaged with applied arts. That environment helped shape me. There were conversations around all this. He had a saying: “Don’t put in too much—less is more.” He was a bit rough, very direct. But that kind of guidance was helpful.

What drew you to creating ceramic art, and what does it mean to you?

Before I finished my interior decoration studies, I met a friend who had a shop. At the time, there were very few contemporary ceramic studios in Greece—almost none. He used to buy traditional ceramics, and I would go with him to visit these studios. The more I went, the more involved I became. I still remember the smell of the kiln firing—very unhealthy, but I loved it. It was love at first sight. The smell, the mess—I loved all of it. Even now, when I touch certain ceramics—not mine—I get this feeling. In Greek, we have a phrase, “like a shiver down your spine.” That’s how it began. I knew instantly that this is it.

I love this.

In the ‘60s and especially the ‘70s, Greek society had a strong sense of community. There was no internet, no cell phones—we interacted more. We danced. We had real friendships. Life wasn’t as aggressive as it is now. People had less, but what they had was richer in quality. Even as a child, I remember having only a few toys—but I cherished each one. Same with materials. Back then, you had one kind of clay. Now, you can call a supplier and choose from dozens. We’ve gained options but maybe lost some of the soul.

How did the atmosphere of 1970s London influence your studies and growth as an artist?

The 1970s were a very special time—something that doesn’t exist anymore. We were the generation after the hippies. ”Back to nature” was the motto. Applied arts had real meaning then. Ceramics, textiles—they all had a purpose and value. There was a cultural peak that lasted until the late '80s. After that, things declined—especially for people working in applied arts. Even in Greece, it was difficult. I knew people who studied applied arts in England, came back, worked for two or three years, and then gave it up because they couldn’t make a living. But in 1970s London, it was a revolution. You appreciated traditional arts.

In Greece, that wasn’t the case. Very few people saw ceramics as contemporary art. When I came back to Greece in 1975, there were maybe 18 people doing what I did. That was it. I remember making ceramics in red clay—terracotta—and people would immediately say, “That’s a flower pot,” even when it clearly wasn’t. That’s how strong the association was. But now things have changed. Now it’s a good era.

Part of your collection features vintage brands. What inspired that work, and what do you hope people take from it?

That’s another interesting story. Around 1991 or 1992, I started developing a new direction. My background in design played a role. Back then, design didn’t really exist in Greece the way it does now. One of my professors, the painter Hariklia Mytara, taught us what was essentially design—though we didn’t call it that.

I’ve always been very social. Since I was 17, I used to go to Monastiraki market—it was much more primitive then—and I would search for interesting objects. One day, I came across some industrial packaging—like biscuit boxes and oil cartons—and it just clicked. It became a game for me. I’d wake up every day thinking, “What’s next?” I started visiting supermarkets, looking for shapes that spoke to me. Some objects weren’t easy to recreate in clay, so I started working with aluminum too. That led me to Habitat. Back then, Habitat was owned by Terence Conran, a major English designer. He sourced traditional objects from Mediterranean countries and reintroduced them through a design lens.

When they opened a store in Greece, I knocked on their door—I’ve never been shy about that. They were kind, not snobbish, and they immediately took my work. I was the first and only Greek artist to work with Habitat at the time. Their policy was to feature one local designer in each country, and they kept my work—the coins—for three years instead of one because it sold so well.

Other objects in my vintage brands collection include biscuits, the aspirin box (also in metal), and a soap brand called Arkadi, which I did in aluminum. In ceramics, I recreated milk cartons from Milko, which is a Greek product.

I also did Nivea, Coca–Cola, and others I can’t remember right now.

Is there a particular piece or project that stands out to you—something you especially loved creating?

That’s a tough one because I work across multiple disciplines—sculpture, design, functional ware. Deep down, functional ware is where I started and what I care about. But I don’t feel I ever fully explored it. Life got in the way, and I had to juggle other work. For the last 20 years, I’ve told myself I’d love to focus only on sculptural work. So, I’m always torn between the two.

How did your uncle, Yannis Moralis, influence your artistic path, and what drives the evolution of your own style?

He was an incredible influence. You mentioned the Hilton façade—that’s how most people know him—but his paintings were so diverse. From realism to abstraction, he explored everything. That’s what makes a true artist: evolution. You start one way and, if you’re truly creative, you feel a need to change. My uncle went from expressive early work to minimal, geometric abstraction.

That need to move forward comes from within. I get bored easily. I can’t make 100 of the same thing. By the 20th piece, I’m ready to switch it up. Some years ago, I made realistic ceramic shoes. I even did installations with them. A museum in Kalamata invited me to exhibit them because they saw a link to traditional Greek costume. It was a huge compliment—but honestly, it was hard to go back to that kind of work. When I was younger, I loved rough textures and dull colors. Now I love porcelain and lighter palettes.

Artists grow. There’s a moment where something ends and something new has to begin. It’s like a restlessness.

I can’t explain it.