From Bondage to Freedom: the Greek Revolution of 1821

- Portes Magazine

- Jan 31, 2021

- 6 min read

"THOSE WHO THINK FREELY, THINK WISELY."

The Greek revolution, η επανάσταση του '21 as we Greeks call it, is a defining moment in Greek history. It gave us the modern nation-state of Greece, and marks the transition of Greece to the modern era. Freedom was costly, and required the bloody sacrifices of courageous men and women who did not hesitate to give their life for the cause. As we prepare to celebrate this momentous occasion, it is a fitting opportunity to reflect on what the επανάσταση was about, what exactly the Greeks fought against in 1821, and how this struggle continues in new forms today.

The Greek insurrection was first and foremost a revolt of an oppressed people who viewed themselves as enslaved by foreign rulers. The famous revolutionary Rigas Feraios, who was assassinated in 1798 while in custody by the Ottomans, his body, along with those of his five comrades thrown into the Danube river, captures the sentiment perfectly in his famous hymn Θούριος, written just a year before he died:

Καλιώνε μιας ώρας ελεύθερη ζωή παρά σαράντα χρόνια σκλαβιά και φυλακή Βetter to have one hour of life as free people than forty years of slavery and prison

Greek War of Independence Hero Rigas Feraios

Feraios and his contemporaries experienced the Ottoman rule as σκλαβιά (enslavement) by άλλον έθνος (another nation), in the words of the Greek revolutionary army leader Theodoros Kolokotronis. The revolution was an attempt of the Greeks to free themselves from the Οθωμανικός ζυγός (Ottoman yoke), a metaphor reflecting the experience of their subjugation as a form of bondage.

How did this come to be? In 1453, Constantinople, the capital of Byzantium, falls to the Ottoman Turks. Byzantium, which lasted from 323 to 1453 AD, is the place and time where Hellenism and Christianity meet. This period was also known as Ρωμανία by the Greeks, (a word that survives in Modern Greek today, and from which the identifiers Ρωμιός and Ρωμιοσύνη are derived).

Greek culture and education transformed with the infusion of Christianity. Ρωμανία developed a glorious medieval civilization which was not theocratic, as some believe, but as historian Anthony Kaldellis tells us, republican in nature ... with civic engagement in decision making at a time when Western Europe was feudal. Byzantium lasted for more than 1100 years as the longest living European empire, yet it is non-existent in European history classes at U.S. schools.

When Constantinople falls, Greece enters the period known as Τουρκοκρατία (Turkocracy), which lasts more than four centuries (as parts of Greece such as Macedonia and Thessaly remained under Ottoman rule into the 20th century). Like the other emerging European monarchies of the time, the Ottoman Empire was organized as a colonial structure. Originating in Central Asia, it expanded westward by conquest of Byzantine territory. In the conquered lands, the Ottomans applied a system of exploitation similar to those found in North and South America, India, and Africa.

After the fall of Constantinople, conquest expands to the entire Balkan peninsula and parts of Eastern Europe. All subjugated Christian nations, now under the Rum millet, struggle to survive under threats of life, discrimination, disproportionate taxation, and Islamization, which included the cruel practice of devshirme - the forcible abduction of young Christian boys, sometimes as young as 2 or 3 years old, to become soldiers in the Ottoman army. Christian girls and young women could likewise easily end up in harems against their or their parents’ will. The women at Zaloggo and Naoussa danced to their death with their own children in order to avoid living as sex-slaves.

The Ottoman rule applied the racialized system familiar in form with other terrible systems of slavery and apartheid. While Western Europe was experiencing Renaissance, Greece entered a period of prolonged darkness. The colonial character of the Ottoman empire and its racist treatment of the Christian minorities is often minimized in public discussions in the U.S. The word “Turkocracy,” which Greeks use to name their experience, tends to be replaced by euphemisms. Yet, despite some variance over time, which at best resulted in systems paralleling regulated apartheid and Jim Crow laws, the Christian populations of the Ottoman Empire were treated as inferior and exploitable "others" called dhimis, or even more offensively, giaour - a term Turks used for the Christian non-believers. Under Ottoman rule, Christians were second class citizens with very few rights.

To paint a picture, Christians lived in distinct quarters, separated from Muslims, and were not permitted to build tall buildings. They were forbidden to mingle with the Turks in social activities, and had to wear distinctive clothing, like the Jews were forced to identify themselves in Nazi Germany. The code of clothing was strict, and Christians were not allowed to wear clothes of luxurious fabrics. Public religious celebrations were forbidden, including the ringing of church bells. Churches were systematically vandalized and eventually turned into mosques. No new churches could be built.

Education in the Greek language was restricted or forbidden, and language was taught at night at the κρυφό σχολειό, (secret school), as commemorated in the children’s poem Φεγγαράκι Μου Λαμπρό, (My Bright Little Moon), which Greek children still sing today. Greeks and other Christians were not allowed to ride horses, and were excluded from civil service and office. Greek farmers did not own the land they worked on, paid extremely high taxation compared to Muslims, and were in practice reduced to serfs. It is no wonder that the Greeks perceived the Ottoman time as a period of bondage and exclusion.

Flag depicting the phrase "Ελευθερία η Θάνατος" (Freedom or Death)

Greeks rebelled often during the 400 years of Turkocracy, until in 1821 they declared a war that succeeded and led to the Modern Greek State of 1830. The first Greek revolutionary government was nominated on January 15, 1822 at the 1st National Assembly of Epidaurus, where a temporary constitution was drafted. The constitution, known as Νόμος της Επιδαύρου (Law of Epidaurus), was expanded and ratified in the 2nd National Assembly in 1823 at Argos, and in it, we find ideas of just government and democratic rule, as well as abolishment of slavery. The Law upholds the principles of freedom and equality:

"Όλοι οι Έλληνες, εις όλα τα αξιώματα και τιμάς έχουν το αυτό δικαίωμα, δοτήρ δε τούτων μόνη η αξιότης εκάστου"; "όλοι οι Έλληνες εισίν όμοιοι ενώπιον των νόμων άνευ τινός εξαιρέσεως ή βαθμού ή κλάσεως ή αξιώματος."

"All Greeks have the right to any office or honor, based solely on their merit. All Greeks are equal under the Law without any exception based on rank, class, or office."

The phrasing reminds us of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. Greek intellectuals such as Adamantios Koraes, who lived in Paris at the time, admired the American revolution, and exchanged letters with Thomas Jefferson.

Most people do not know that Haiti was the first country in the world to recognize Greece as an independent state. And this was no accident. Haiti was a slave colony of France, and the Haitian Revolution led to independence in 1804 and the creation of the sovereign state of Haiti. The Greek revolutionaries thought of the Haitians as natural allies, and sent a letter to the President Jean-Pierre Boyer praising the courage of the Haitian people and asking for help. Haiti, of course, was a poor country and could not offer financial aid. Food and coffee were said to be promised along with one hundred Haitian volunteers to fight in the Greek struggle, who sadly, perished on the Atlantic ocean en route to Greece.

Haitian President Boyer expressed solidarity with the Greek struggle because he recognized that it was a fight for liberation from bondage, similar to the struggle of his own people. In his own words, in a January 1922 letter sent to the Greeks, he says:

"Your beautiful and just cause, as well as the resulting first successes, are not indifferent to the Haitians who, like the Greeks, for a long time bent the neck under a painful yoke and who, with their chains, crushed the heads of tyranny. Citizens, forward to your compatriots the warmest regards that the Haitian people send in favor of their liberation."

On March 25th, as we celebrate, let us remember that the message of the Greek revolution is now more urgent than ever. It is our duty to think and act as free people. As so succinctly put in the words of Rigas Feraios:

"Οποιος ελεύθερα συλλογάται, συλλογάται καλά."

"Those who think freely, think wisely."

_____________________________

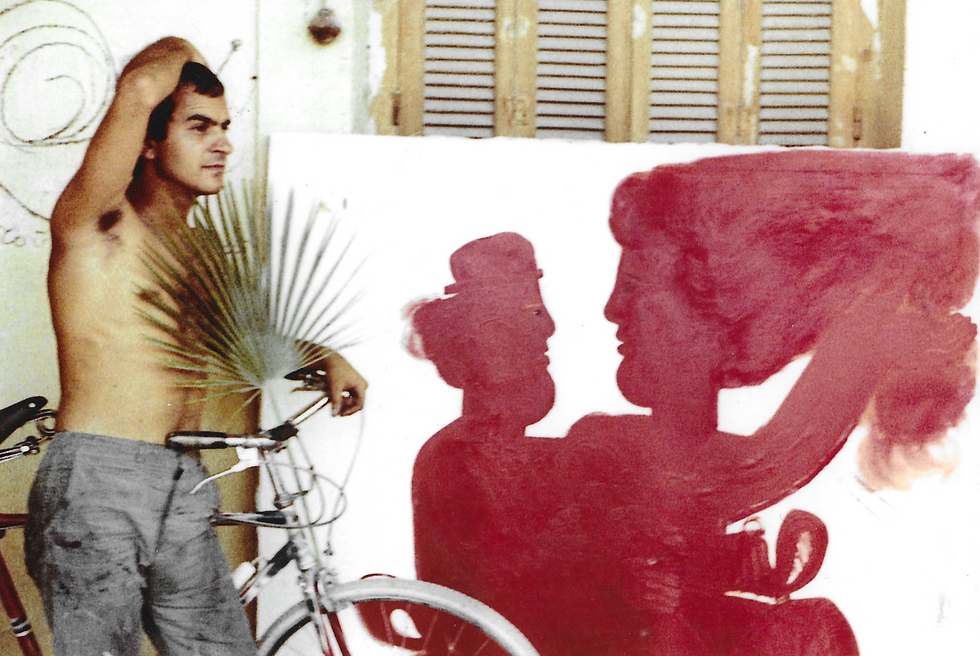

WORDS: Anastasia Giannakidou PHOTOS: National Gallery Alexandros Soutsos Museum | Benaki Museum

Dr. Anastasia Giannakidou is a Professor of Linguistics and the College at the University of Chicago. She studied Classical Philology and Linguistics at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece, and received her PhD in Linguistics from University of Groningen, the Netherlands. She is one of the founders and the director of the newly established Hellenic Studies Center at the University of Chicago. She is also a co-director of the Center for Gesture, Sign and Language, and a collaborator in the Bilingualism Matters initiative in Chicago.