Rock of Liberty: HYDRA

- Jan 31, 2021

- 3 min read

"HYDRA KNEW HER STORY, AND HER CHILDREN, WHETHER ON THE ISLAND OR SCATTERED TO THE FOUR WINDS, HAD THE HISTORY DRILLED INTO THEM."

Choosing among the most exquisite Greek islands is a delightful and difficult task, yet Hydra always seems to make the shortlist. An amphitheater of cubist perfection and ceramic tiles, with stately mansions hewed out of the native granite, it is hardly a wonder that the isle has inspired painters and poets. Spared the tyranny of the automobile and the destructive scourge of concrete "progress," the island is a glamorous hideaway from the ordinary.

Less known but hardly hidden is the island's glorious past. No, not a distant past. Hydra's glory is recent. In a land as ancient as Greece, this hulking chunk of granite rising vertically from the Saronic Gulf, one of the oldest seaways, has been relatively absent from history until a series of events suddenly put this island on the map.

The seventeenth century was a rough time in the Aegean. While the Ottomans and Venetians battled for control of the Peloponnesian mainland just opposite Hydra, waves of people took refuge on the island. Prior to this, only occasional shepherds visited Hydra. Supporting a larger population on what is essentially a barren rock, these islanders, like Greeks from time immemorial, took to the sea.

By the eve of the Greek War of Independence in 1821, this island had the largest fleet in the Eastern Mediterranean. Mansions sprang up from the harbor, built by daring captains and shipowners who had grown rich in less than a generation. These wily mariners flew various flags when "convenient" and navigated the politics and economics of the Napoleonic and Russo-Ottoman conflicts with the same skill as they piloted their ships.

When the war began, the Hydriots contributed their ships, fortunes, and lives to the cause. This tiny island took on the Ottoman realm, and, together with two other diminutive Aegean islands, Spetses and Psara, turned the Aegean Sea into a Greek lake. The price of victory was steep, as the island never recovered its shipping fortunes.

Thus, as quickly as Hydra rose in prominence, it fell. Many of the island's houses turned to ruins, their grey stones blending into the granite landscape. Grandchildren of the heroes of 1821 added further members to the honor roll of Hydriots in the Balkan Wars of 1912 - 1913, yet, the island had passed out of history again.

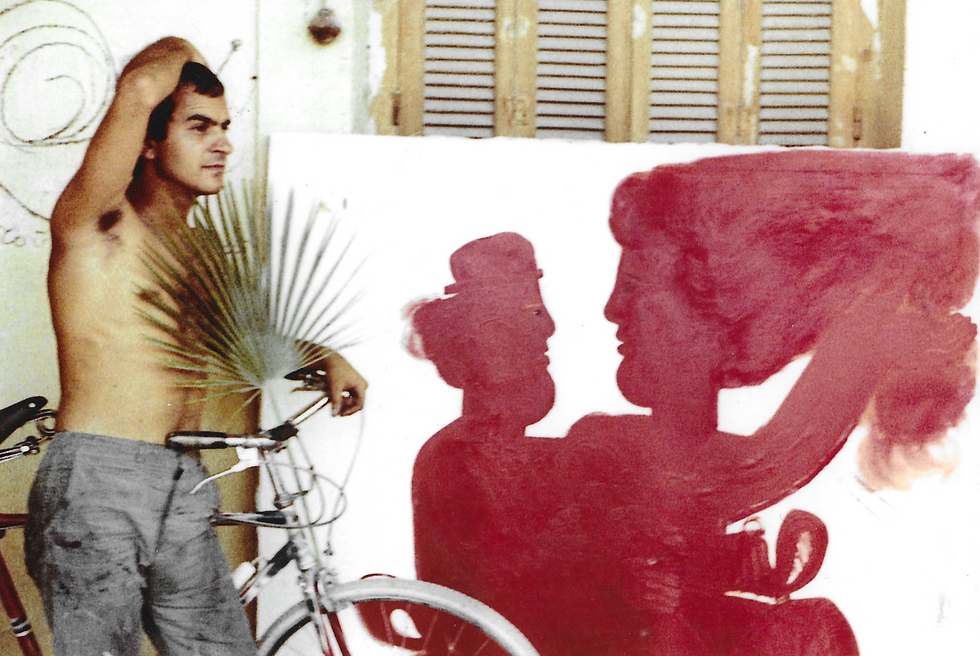

In the postwar era, history, or at least, celebrity, returned to Hydra. The island's picture perfect port, rising like a Greek theater from the harbor, its proximity to Athens, and its ethereal light brought artistic types to the island. These included repatriated natives such as the painter Nikos Ghika, or the British war hero and writer Patrick Leigh Fermor, perhaps the greatest biographer of Modern Greece. Add to this the crooner Canadian Leonard Cohen, and other celebrities over several decades, and the island became a fixture.

Poverty and topographical challenges spared Hydra the fate of other venues - concrete disfigurement and the ubiquity of the motor vehicle. Careless Hydra was a living museum of its glory days - though most visitors were simply too captivated by its beauty to inquire about its story.

Hydra knew her story, and her children, whether on the island or scattered to the four winds, had the history drilled into them. Greek schoolchildren rote-learned of the exploits, but the island waited to bring its history to context. That time is at hand, as Greece celebrates her two hundredth birthday in 2021.

_____________________________

WORDS: Alexander Billinis

PHOTOS: Alexander Billinis | Museum of Hydra

Alexander Billinis is an international banker and author who's spent much of his career in the Europe of the Financial Crisis. His book, The Eagle has Two Faces: Journeys through Byzantine Europe, is a travelogue of the Balkans, Asia Minor, and Southern Italy. His second book, a novel, Hidden Mosaics: An Aegean Tale, reveals the common heritage of an Aegean littoral now divided up by exclusivist states.